Background

By definition, competence is a collection of related abilities, commitments, knowledge, and skills that enable a person to act effectively in a job or situation.

Competency is measurable and can be developed

through learning & development. The term "competence" first

appeared in an article authored by R.W. White in 1959 as a

concept for performance motivation. The term gained traction in 1973

when David McClelland wrote a seminal paper entitled, "Testing

for Competence Rather Than for Intelligence". The term, created by

McClelland, was commissioned by the State Department (USA) to explain

characteristics common to high-performing agents of embassy, as well as

help them in recruitment and development. It has since been popularized

by Richard Boyatzis, and many others who used the concept in performance

improvement.

Its uses vary widely, which has led to

considerable misunderstanding. Some scholars see "competence" as a

combination of practical & theoretical knowledge, cognitive skills, behavior,

and values used to improve performance; or as the state or quality of being

adequately or well qualified, having the ability to perform a

specific role. For instance, management competency might include

system thinking and emotional intelligence, as well as skills in influence

and negotiation.

Studies on competency indicate that competency

covers a very complicated and extensive field, with different scientists having

different definitions of competency. Few perspectives on competency by various

researchers are:

Competency is an action that might be different the next time a person needs to act. If someone is able to do required tasks at the target level of proficiency, they are considered "competent" in that area. In emergencies, competent people may react to a situation following behaviors they have previously found successful. To be competent a person would need to be able to interpret the situation in the context and have a repertoire of possible actions to take. Being sufficiently trained in each possible action included in their repertoire can make a great difference. Regardless of training, competency grows through experience and the extent of an individual's capacity to learn and adapt. However, research has found that it is not easy to assess competencies and competence development.

What

Is Speed to Competence?

Put simply, it’s the measure of time spent upskilling an individual or group with the skills, knowledge and confidence to apply in their lives (or at the workplace). By understanding and measuring the distance between subject delivery and retention, we are more informed to make necessary learning adjustments to speed up competence.

Accelerating time to competence is taking

precedence in many organizations today. No one likes to waste time (especially

when it costs money). Accelerating time to competence also impacts employee

engagement and satisfaction. In fact, according to research by the Wynhurst

Group: “22 percent of staff turnover occurs within the first 45 days of

onboarding with the cost of losing an employee in the first year estimated to

be at least three times the salary”.

Correlation with Employee Engagement

During the tenure of an employee, job roles change, technology evolves, and new skills are continuously required. Few would argue that a critical part of keeping employees engaged is providing learning approaches that allow them to quickly develop new skills and to build a set of competencies that provide a springboard for a successful career. It’s unanimously agreed upon that in today’s environment, formal instructor-led training and online courses alone are not enough to drive successful performance outcomes.

For organizations, accelerating speed to competency is closely linked with accelerating time to ROI; competency effects user productivity, organizational efficiency, and project success. In a world where technology becomes obsolete in the blink of an eye and competitors are more aggressive, every bit of time counts. Those that contribute the most to organizational objectives are those who are better trained and are up to speed to the latest technologies, standards, or procedures.

While managers may want to apply these

practices in broad strokes, it can be beneficial to take a more focused

approach. Accelerating speed to competency requires a plan, commitment, time, and

energy. Focusing on solving the right problem is crucial for

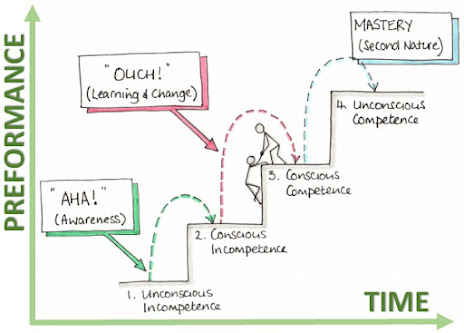

accelerating time to competence. To better illustrate why we first need to

focus on solving the right problem with a competency plan, we need to

understand the Four Stages of Learning developed by Noel Burch in the

1970s:

While not all individuals will start at the same phase, it is important that managers provide appropriate resources to aid all end users in working through this process based on individual needs. Deliberate practice, therefore, simply stated says that – competence requires practice. If managers really want to accelerate time to competence, designing and developing a learning program with consistent and measurable practice throughout is key. In the world of learning, practice can be defined as any activity that requires the application of knowledge, with the applied interaction of end users.

Systemic

Approaches For Accelerating Competency in Organizations

How Does Competence Change Over Time?

If there is one thing to keep in mind, it’s

that competence itself is fluid and occurs as we learn to do things.

There are many different descriptions of what that the journey towards

competence looks like, but there are a few common themes on the range from

beginner to expert.

Most models of skill acquisition look at proficiency scales as being linear, but in actuality, the journey can be more circular or branching, depending on a number of variables, such as complexity, pace of change, and the frequency that the activity is put into practice. For example, let’s take a common activity that a large number of adults can do competently – driving a car – and see how this model of skill progression applies.

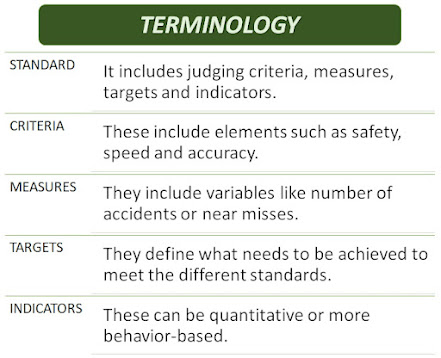

Get The Semantics Right

Many competency-related projects have failed because of cognitive barriers. The domain of competency mapping is complex, but it does not have to be complicated. Clarity, consistency and accuracy in labeling are important.

A job role combines disciplines, functions and

assets and typically has multiple levels. For example, a mechanical engineer

may support plant operations or may do research in R&D. The discipline is

the same, but the functions are different. Alternatively, a technician, an

operator and a process engineer may support a plant. The disciplines are

different, but the function is the same.

Competence is a stage in the development of a person and Competency is knowledge, skills and other attributes required to execute actions in a job context that meet certain defined standards. The other attributes include all the deeper or hidden dimensions of competency, such as attitude, values, traits, self-image and self-regulation. There is confusion about the use of these terms.

Learning Approaches for Accelerating Speed to Competency

The goal of learning is not simply to provide knowledge, content and skills — but to prepare learners faster, there must be some productive mindset changes towards what really should happen in life. When it takes a long time to achieve proficiency, organizations could lose money while handling errors. Unless we measure proficiency in learning interventions in the same way as in real life, any amount of knowledge will not help speed up proficiency. Mastering tasks or activities, or skills away from the context in which outcomes must be produced does not contribute towards speeding up competencies.

Content Curated By: Dr Shoury Kuttappa

Comments

Post a Comment