A Short Story- Jonas Salk and the Polio Vaccine:

In 1952, polio killed more

children than any other communicable disease. Nearly 58,000 people were

infected. The situation was on the verge of becoming an epidemic and the

country desperately needed a vaccine.

In a small

laboratory at the University of Pittsburgh, a young researcher named Jonas Salk

was working tirelessly to find a cure. (Years later, author Dennis Denenberg

would write, “Salk worked sixteen hours a day, seven days a week, for years.”).

Despite all his effort, Salk was stuck. His quest for a polio vaccine was

meeting a dead end at every turn. Eventually, he decided that he needed a

break. Salk left the laboratory and retreated to the quiet hills of central

Italy where he stayed at a 13th-century Franciscan monastery known as the

Basilica of San Francesco d'Assisi.

The basilica could not have been more different than the lab. The architecture

was a beautiful combination of Romanesque and Gothic styles. White-washed brick

covered the expansive exterior and dozens of semi-circular arches surrounded

the plazas between buildings. Inside the church, the walls were covered with

stunning fresco paintings from the 14th and 15th centuries and natural light

poured in from tall windows. It was in this space that Jonas Salk would have

the breakthrough discovery that led to the polio vaccine. Years later, he would

say…

Today, the discovery that Salk made in that Italian monastery has impacted millions. Polio has been eradicated from nearly every nation in the world. Did inspiration just happen to strike Jonas Salk while he was at the monastery? Or was he right in assuming that the environment impacted his thinking? And perhaps more importantly, what does science say about the connection between our environment and our thoughts and actions? And how can we use this information to live better lives?

The Link Between Brains and Buildings

Researchers have

discovered a variety of ways that the buildings we live, work, and play in

drive our behavior and our actions. The way we react and respond is

often tied to the environment that we find ourselves in.For example, it

has long been known that schools with more natural light provide a better

learning environment for students and test scores often go up as a result.

(Natural light and natural air are known to stimulate productivity in the

workplace as well.)

Additionally, buildings with natural elements built into them help reduce

stress and calm us down (think of trees inside a mall or a garden in a lobby).

Spaces with high ceilings and large rooms promote more expansive and creative

thinking.

So what does this link between design and behavior mean for us? Change

Your Environment, Change Your Behavior. Researchers have shown that

any habit you have — good or bad — is often associated with some type of

trigger or cue. Recent studies (like this one) have shown that these

cues often come from your environment.This is important because most of us live

in the same home, go to the same office, and eat in the same rooms day

after day. And that means you are constantly surrounded by the same

environmental triggers and cues.

If our behavior is often shaped by our environment and we keep working,

playing, and living in the same environment, then it’s no wonder that it

can be difficult to build new habits. Studies show that it is easier to

change our behavior and build new habits when we change our environment. We are more

reliant on environmental triggers than we’d like to think. In one study conducted

on “habits vs. intentions,” researchers found that students who transferred to

another university were the most likely to change their daily habits. Those

habits were easier to

change than the control group because they weren’t exposed to familiar external

cues.

The mirrors research on the stimulus control theory, or the effect of a stimulus on behaviour shows that techniques involving stimulus control have even been successfully used to help people with insomnia. In short, those who had trouble falling asleep were told to only go to their room and lie in their bed when they were tired. If they couldn’t fall asleep, they were told to get up and change rooms.

Strange advice, but over time, researchers found that by associating the bed with ‘It’s time to go to sleep’ and not with other activities (reading a book, just lying there, etc.), participants were eventually able to quickly fall asleep due to the repeated process: it became almost automatic to fall asleep in their bed because a successful trigger had been created. Perhaps we are more like Pavlov’s dogs than first imagined, it is interesting to see how small cues can greatly impact our behaviour.

If we are struggling to think creatively, then going to a wide open space or moving to a room with more natural light and fresh air might help us solve the problem. (Like it seemingly did for Jonas Salk). Meanwhile, if we need to focus and complete a task, research shows that it’s more beneficial to work in a smaller, more confined room with a lower ceiling (without making ourselves feel claustrophobic, of course). And perhaps most important, simply moving to a new physical space — whether it's a different room or halfway around the world — will change the cues that we encounter and thus our thoughts and behaviors. Quite literally, a new environment leads to new ideas.Putting This Into Practice

In the future, we hope that architects and designers will use the connection between design and behavior to build hospitals where patients heal faster, schools where children learn better, and homes where people live happier.That said, we can start making changes right now. We do not have to be a victim of our environment. We can also be the architect of it. Here is one simple 2-step prescription for altering our environment so that we can stick with good habits and break bad habits:

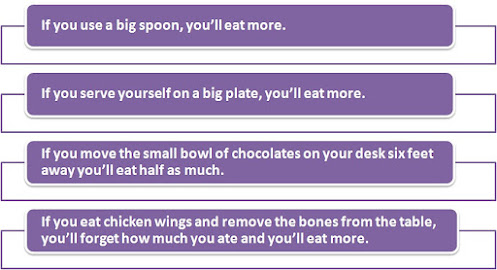

Our

environment can also be tweaked to make certain tasks more difficult or easier

to do. Here are some examples…

By designing our environment to encourage the good behaviours and prevent the

bad behaviours, we make it far more likely that we’ll stick to long-term

change. Our actions today are often a response to the environmental cues that

surround us. If we want to change our behaviour, then we have to change

those cues.

Comments

Post a Comment